3:00 DO FISH HAVE RIGHTS?

I started this week’s call with an update on a fish story I told a few weeks ago about the lone koi fish I had in my garden pond, the sole survivor of a holocaust perpetrated earlier in the spring by migrating blue herons. He was hiding under a rock, traumatized I assumed, and not eating long past the end of his winter dormancy.

I considered leaving him to his own devices. “Eat or don’t eat,” I thought, absolving myself of responsibility. “If he dies,” I reminded myself, “the pond will be a lot easier to take care of.”

But instead I decided to go to the fish store and buy five new koi. When I introduced them to the pond my original fish immediately (I’m talking within three seconds) swam out from under his rock and began schooling with them. Today, six weeks later, they are a happy fish family, swimming, eating, mating, playing in the waterfall and in general living the koi dream.

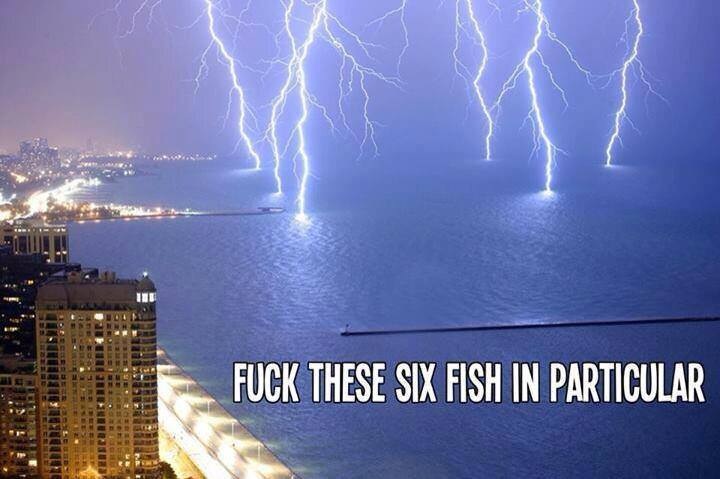

How God kills fish.

What spurred my decision to add new fish was research I had posted a few days earlier by fish biologist Culum Brown revealing how fish are intelligent, social, emotional beings on par with many mammals.

Fast forward to this week, when two of my favorite bloggers, Andrew Sullivan of the Daily Dish and Ezra Klein of VOX, published an extended interview with Professor Brown. In it he talked about the reality of commercial fishing in our oceans, and the suffering it causes the fish…

Every major commercial agricultural system has some ethical laws, except for fish. Nobody’s ever asked the questions: “What does a fish want? What does a fish need?”

I think, ultimately, the revolution will come. But it’ll be slow, because the implications are huge. For example, I can’t think of a way to possibly catch fish from the open ocean in a massive commercial way to meet demand that would be anyway near our standards for ethics if we think of them like other animals. Currently, you go out, you catch a bunch of fish, you crush most of them to death in a net, you trawl them up from the bottom of the sea – which causes barotrauma for most of them – you dump them on a deck, half suffocate to death, the ones you don’t want get thrown overboard and die anyway, and the ones you keep go on ice, just to preserve the flesh for market reasons.

How do you do that in a way that has the fish’s interests involved to any degree? You can’t. So it’s not surprising that there is some fierce opposition to this idea. It would mean a massive change in the way we do things.

It also means a massive change in my (and perhaps your) delusion that if we’re eating fish we’re contributing less to the suffering of our animal brethren.

8:50 DEMOCRACY AND DEVELOPMENT

For my main story this week I note a new meme arising among political thinkers: the idea of the modern yet non-liberal state. Two of my favorite columnists, Fareed Zakaria of the Washington Post, and David Brooks of the New York Times, both wrote on this topic this week. Both were spurred by a remarkable speech given by the president of Hungary, Viktor Orban, who as he begins his second term in office gives voice to the idea of a non-Western, non-liberal yet modernized country.

As David Brooks wrote in his Monday column “The Battle of Regimes”:

On July 26 … Prime Minister Viktor Orban of Hungary gave a morbidly fascinating speech in which he argued that liberal capitalism’s day is done. The 2008 financial crisis revealed that decentralized liberal democracy leads to inequality, oligarchy, corruption and moral decline. When individuals are given maximum freedom, the strong end up stepping on the weak.

The future, he continued, belongs to illiberal regimes like China’s and Singapore’s — autocratic systems that put the interests of the community ahead of individual freedom; regimes that are organized for broad growth, not inequality.

Orban’s speech comes at a time when democracy is suffering a crisis of morale. Only 31 percent of Americans are “very satisfied” with their country’s direction, according to a 2013 Pew survey. Autocratic regimes — which feature populist economics, traditional social values, concentrated authority and hyped-up nationalism — are feeling confident and on the rise. Eighty-five percent of Chinese are very satisfied with their country’s course, according to the Pew survey.

Fareed Zakaria commented on Orban’s speech in his column titled “The Rise of Putinism”:

The crucial elements of Putinism are nationalism, religion, social conservatism, state capitalism and government domination of the media. They are all, in some way or another, different from and hostile to, modern Western values of individual rights, tolerance, cosmopolitanism and internationalism. It would be a mistake to believe that Putin’s ideology created his popularity — he was popular before — but it sustains his popularity.

Orban has followed in Putin’s footsteps, eroding judicial independence, limiting individual rights, speaking in nationalist terms about ethnic Hungarians and muzzling the press.

So Putinism is pre-modern in its interior quadrants, stressing conformity over freedom and collective identity over individual rights. But note that nobody is advocating going back to a world that is pre-modern in the exterior quadrants. The new autocrats are not agrarian Luddites. On the contrary, their goal is to create organized, industrialized, information-rich, modern economies. Viktor Orban makes this clear in his speech:

…While breaking with the dogmas and ideologies that have been adopted by the West and keeping ourselves independent from them, we are trying to find the form of community organisation, the new Hungarian state, which is capable of making our community competitive in the great global race for decades to come.

There is an intelligence to this thinking. The simple fact is that the great majority of people worldwide are pre-modern in their interiors, in their thinking and ways of relating. They are prone to romantic myths of ethnic superiority, strong-man saviors and great battles against an evil “other”. They are confused by pluralism, repelled by sexual liberation and turned off by the counter-culture aesthetic that inevitably arises with modernity and postmodernity. This is true of traditionalist people in every country; yet some countries have higher proportions of people with pre-modern interiors (Russia and China versus the countries of Western Europe, for instance) and thus their developmental centers of gravity are lower.

Leaders who can harness pre-modern impulses are very powerful and popular in their own societies. Today Vladimir Putin’s approval rating, at 80%, is double that of Barack Obama’s. When conditions are favorable, as they have been in both Russia and China for the last twenty years, and huge swaths of population are moving out of poverty into decent modern conditions (in housing, employment, education, medicine, and if not full human rights then at least a relaxation of the police state), then people are content and able to experience interior development at a healthy, sustainable rate.

Leaders who can harness pre-modern impulses are very powerful and popular in their own societies. Today Vladimir Putin’s approval rating, at 80%, is double that of Barack Obama’s. When conditions are favorable, as they have been in both Russia and China for the last twenty years, and huge swaths of population are moving out of poverty into decent modern conditions (in housing, employment, education, medicine, and if not full human rights then at least a relaxation of the police state), then people are content and able to experience interior development at a healthy, sustainable rate.

When conditions are unfavorable, however, the new autocrats will ratchet down to appeal to the more ethnocentric and xenophobic impulses of the population’s premodern worldview, which is organized around finding and defeating an enemy, whether it is the enemy abroad (the West is plotting against us) or the enemy among us (homosexuals are corrupting our youth with degenerate values).

The evolutionary question is can the new autocrats contain and metabolize these pre-modern impulses – within their people and within themselves – in a way that moves their countries forward to a mature interior modernity, without falling into the bad old grooves of isolationism and militarism. Russia under Putin is flirting with the latter with his misadventures in Ukraine. And China, though more rooted in economic internationalism, also shows some signs of the same with its military buildup and territorial assertions over islands in the South China sea.

The evolutionary question is can the new autocrats contain and metabolize these pre-modern impulses – within their people and within themselves – in a way that moves their countries forward to a mature interior modernity, without falling into the bad old grooves of isolationism and militarism. Russia under Putin is flirting with the latter with his misadventures in Ukraine. And China, though more rooted in economic internationalism, also shows some signs of the same with its military buildup and territorial assertions over islands in the South China sea.

One thing is clear: the more a culture develops in its interiors the more open, prosperous and peaceful it becomes. What is less clear is how liberalism and democracy play into that process. We used to think democracy led to development, but one of the great lessons of the 21st century so far is that democracy can come too soon: witness the Maliki government in Iraq and Hamas in Gaza, both democratically elected. Now we realize that the trajectory is probably the other way around: development leads to democracy. The ground in-between is the territory being charted by our unlovable new breed of autocrats.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | RSS

Hi Jeff,

I missed last weeks call; but this conversation is Big. Are we breaking down faster than we are walking up? Interiors awake at the Integral, 2nd consciousness levels are less than 5% and the world breaking down, still at pre-modern or moving into orange, around 70%, holding the conveyor belt with only a few breaking through into the more pluralistic perspectives. And, of course, we need the spring board of post modern at Green to jump into Integral. What to do…whats next for US, as Integralists all over the world, to help accelerate this interior awaking.

Good questions, Linda. One response I’d make is that each stage is so much more powerful than the previous one that whole-system evolution doesn’t rely on gross numbers. Ken Wilber has pointed out that modernity came into the world (however imperfectly) when only 10% of the population was at the modern altitude. I’m noting more and more integral thinking coming out of people that are not self-consciously integral, so that gives me hope.

Love Daily Evolver, Jeff. Just want to say how much I appreciate you, what you’re doing, and this great work. Feels so great to see you hitting your stride like this. Keep up the great work and thank you for creating it !

Kosmic hugs,

Stuart

Absolutely brilliant analysis of development and democracy (and autocracy). Bravo Jeff! Love you!

Thanks my friend!

It seems to me there is a confusion here, the object of Democracy is not development, it is the practice of freedom amongst equals. To believe freedom leads to oppression is to believe man is inherently evil, that left to its own devices mankind will choose the worst path. The mith here is that there can be an enlightened leader to deliver us from our inherent desire for damnation… No good will come from leaders like Putin, Castro, Maduro, or their likes. It is the same trap of a better future than the now.

Here in Brazil we have an important thinker (Augusto de Franco) that is working new concepts of Democracy and Social Networks, i wish you guys new more of his work, which the Integral Comunity may read initially as green and anti hierarchy but it actually is radically Pro-Democracy.

De Franco’s work in my opinion fills the gap left by the idea that green is only a troubled and transitional level. Actually i believe we have not yet seen a fully developed and healthy green. In my opinion we are mostly at a rational level, dreaming of Integral and affraid of the necessary letting go of Egocentrism to become trully pluralistically enlightened, only then we will be able to start to get the feel of what integral (in a worldwide communal sense) is like.

What i mean is that there is an immense ammount of work in green, and that means re-informing the communities that would be tempted to need an autocratic Emperor as their leader of their intrinsic value, and rightfull place. Development can be over rated, freedom on the other hand is necessary as the air we breathe…

Thanks Antonio. I’ll check out Augusto do Franco. No doubt that there is plenty green yet to come online. As I’ve pointed out in other posts, the leading edge of evolution tends to come online through art and technology, and the lagging edge consists of politics and economics, which even in developed countries are currently at the stages of traditional and modern.

And what follows is that without freedom what you call development is only a repetition of the past, leading to a very limited future, as interpreted by a governing elite, instead of true growth (in every human aspect) of being connected to the (Gebserian) Originality of the present. Although there is a growing through levels there is no “path” to the future, no trail that everyone else on this planet must follow in order to become actualised.

Freedom is first in order to anyone, or any group of people to find their own original connection tho the all. We must find ways to offer that same freedom and original purity to anyone, in any level of the spiral, believing their own inner momentum will find original fulfilment, Putin out of equation.

I haven’t listened to the full conversation but have to say re: the fish story – ever since being a kid & going fishing with family I was disturbed when the fish would be left to flop around in the bin, eventually suffocating to death. I’m really pleased that people are now beginning to understand the not-okness of this. I still eat meat, in small quantities & am fortunate enough to live rurally where organic homekill is the norm. I want my meat to be from an animal whose gift to me is recognised &honoured. All life has value & even my lettuces get treated as a creature giving up its life to benefit mine.

Looking forward to hearing the full talk, it’s always so informative & stimulates deep thought & vigorous conversation.

Thanks, and yes, this is where I’m landing as well. There’s no doubt that life feeds on life, but we do want to partake in this process with awareness and reverence that honors all beings.

Great talk, as always! Thank You!

One thing struck me though–so I had to look it up:

You quoted Viktor Orban as starting out his argument against liberal democracies by saying that they inevitably end up having the strong ones crush the weak ones, and I guess by extension he was arguing that illiberal democracies weren’t doing that. This simply seemed incorrect. He seemed to use a failing of western democracies that currently gets wide press and then simply let everybody assume that his less liberal system would be better in this regard. I looked up Income inequality in China, as an example, and it seems that my assumption was correct: It is even worse than in the West:

http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-04-30/chinas-income-inequality-gap-widens-beyond-u-dot-s-dot-levels

So I think it is more the case that even in this regard things are generally getting better as we move up the ladder of evolution–we are just still far away from perfect–and there is a certain danger of less evolved altitudes using the limitations of more evolved altitudes as an argument for sliding back.

…I am partially writing this because I am also so surprised and somewhat shocked at how many of my (very intelligent) friends, who seem to be mostly centered on Green, can be seen on Facebook arguing for Putin (against Ukraine and the West) and how it seems Russia is very adept at taking advantage of these sentiments: When I first watched RT I also loved their anti-western-establishment message (until I realized where that message came from). So, it is interesting that a more red-amber altitude (which my intuition tells me is more where Putin, Russia, China, etc. are centered on) actually has the capacity to consciously take advantage of the anti-orange feelings of Green in their propaganda.

One would think a lower altitude would lack the sophistication to manipulate higher altitude opinions like that?

Actually, Jeff–I would love to hear your insights into some of the goings-on around RT in specific. It seems there is a real information war going on, with general opinion tilting against it (reporters who left RTi appearing on John Stewart & other shows) but a significant counter-culture on the left AND right (but more the left, as far as I can tell) tilting much more in favor of RT and against the “Western establishment media”. (Or is it just me traveling in those Facebook circles???)

I see a strange alliance of some of the green with red-amber against orange and wonder where that will lead.

Jeff, when I wrote my previous comments I had not listened to the complete recording yet, so: Thank you so much for replying to my soccer comment! 🙂